Are animals in herds selfish?

|

Flock of juvenile herring gulls, Oregon coast |

Herring gulls, Larus argentatus, flock at the seashore. Juveniles

with dull brown coloration are noticably different from adult; adults of

both sexes are mostly white, with grey/brown wings and darker coloration

on their tails (see picture of adult, below). Juveniles are segregated from

the adults, which live in much less cohesive flocks. Gulls within flocks

watch each other and intensely compete for food items, such as crabs. Using

other individiduals as cues for locating food is a key "selfish"

element in holding the flock together. Also, by staying near others, the

gulls can observe their responses to approaching theats, such as hawks or

foxes, and can take advantage of the visual confusion of many birds taking

simultaneously taking flight it a predator comes near. Adult herring gull |

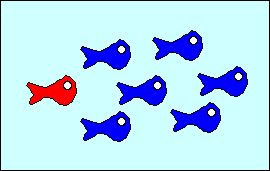

| A school of marine fish. These will scatter if a predator darts in their midst, creating visual confusion. Some positions in the school, particularly the rear, are more vulnerable than others, creating the possibility of competition for locations within the school. |

Elgar, M. A. 1986. House sparrows establish foraging flocks by giving chirrup calls if the resources are divisible. Anim. Behav. 34:169-174.

Hamilton, W. D. 1971. Geometry for the selfish herd. J. theor. Biol. 31:295-311.

page 8-*

copyright ©2001, 2002 Michael D. Breed, all rights reserved